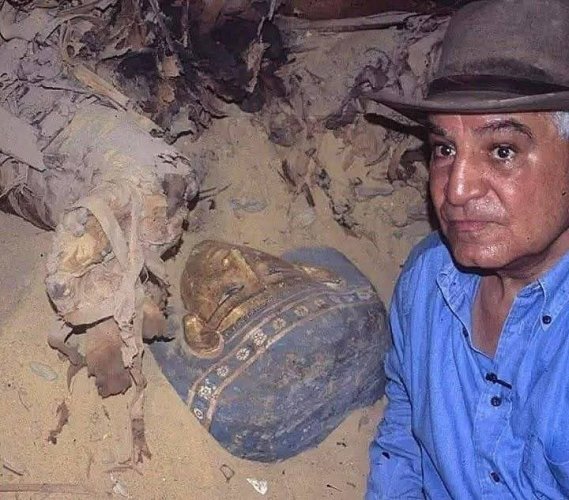

Mummy & coffin of Tamit

Third Intermediate Period, 25th Dynasty, c. 722–664 B.C.

Likely from Thebes. Now at the Museo Egizio. Cat. 2218/02. Cat. 2218/01

Examination of Tamit's remains reveal that she died at a young age and was interred in an anthropoid wooden coffin, typical of the period.

The inner coffin is richly adorned with traditional funerary imagery: a Weighing of the Heart scene from the Judgment of the Dead, a depiction of the wrapped mummy, protective Wedjat eyes, a solar disc, and life symbols such as the ankh. The rear of the coffin bears a painted Djed pillar, symbolising stability and the god Osiris. These decorative elements reflect the enduring spiritual beliefs of Ancient Egyptian religion, which remained prominent under the Nubian rulers of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty.

Despite the care given to her burial equipment, Tamit’s mummification was notably clumsy when compared to earlier standards. Clinical investigations, including C.T. scans, revealed that her brain and internal organs were not fully removed, a key step in traditional embalming. Instead, only partial evisceration and excerebration were performed, with traces of soft tissue still present within the body.

Such an embalming method aligns with certain embalming practices of the time, as mummification during the Third Intermediate Period and the 25th Dynasty often varied in quality. Some mummies from this era show evidence of improvised methods, such as filling the body cavity with hardened mud or omitting transnasal brain removal entirely, allowing the brain to decompose within the skull. These cost-cutting or hastily executed techniques suggest that while religious symbolism remained vital, practical execution could differ depending on social status or available resources.

Tamit herself presents a remarkably lifelike appearance. Her head and face, though darkened by the embalming process, remain well-preserved, and she retains a full head of fine, reddish-brown hair, cut with a distinctive blunt fringe, a striking and humanising detail that bridges the millennia. Though her embalming was imperfect, Tamit was nevertheless afforded the rituals and iconography believed to ensure her passage to the afterlife, affirming the continued significance of funerary tradition in Late Period Ancient Egypt.

Read more:

https://egypt-museum.com/tamit/